By Rose Simpson

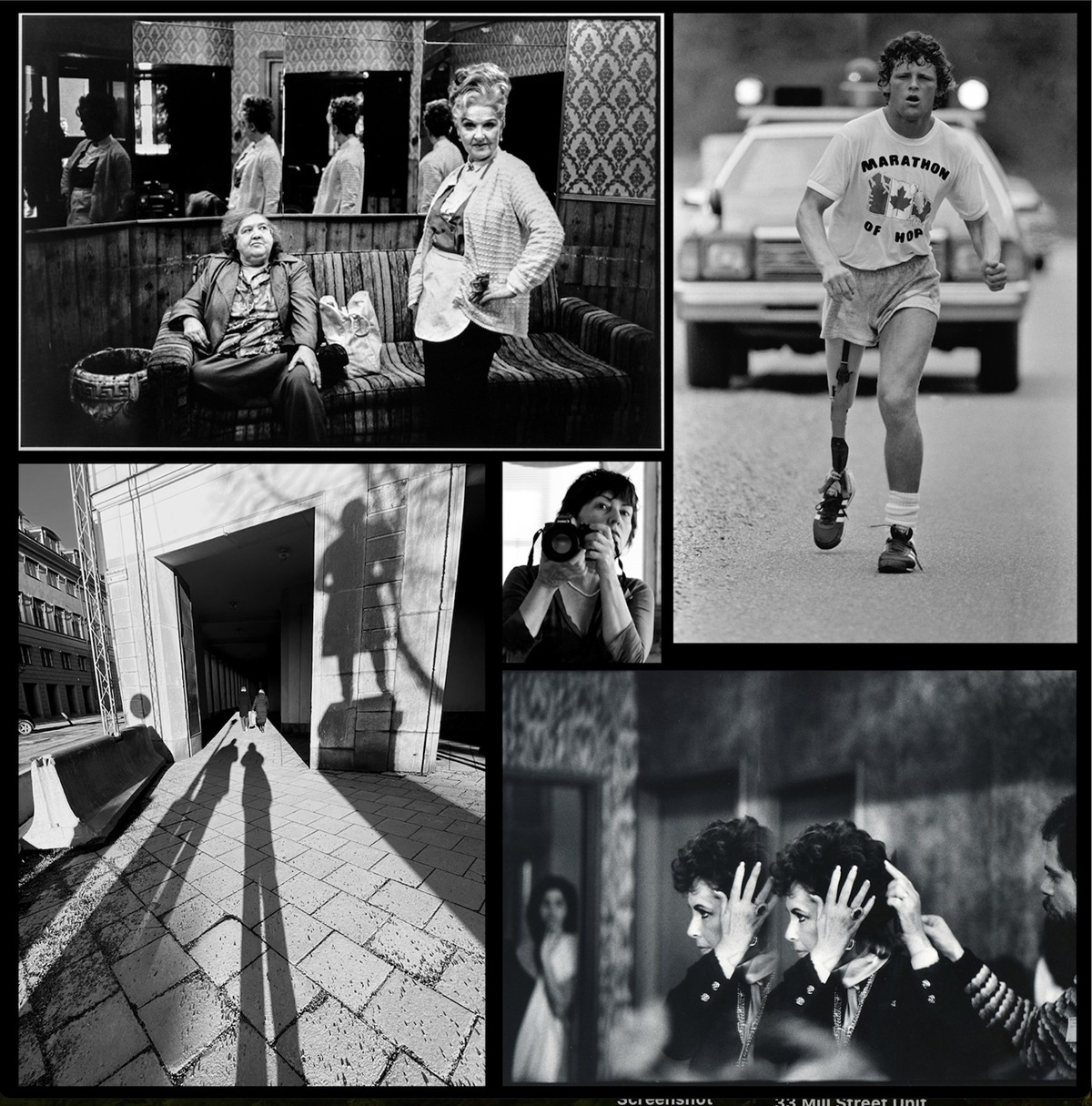

Gail Harvey was working the night photo desk at United Press Canada (UPC) in 1980 and recalls seeing daily images of 22-year-old amputee Terry Fox, the now-legendary lone runner traversing the Canadian landscape to raise awareness and money to cure the cancer that was killing him.

“I thought this guy was incredible,” says Gail, who has parlayed her love of photography into a successful career as both a shooter and acclaimed filmmaker. “I wanted to know more about him.”

Gail offered her services to Terry’s team on her days off. She wanted to document his journey on the Ontario leg of his Marathon of Hope tour, which began in St. John’s Newfoundland April 12, 1980, and ended tragically in Thunder Bay a few months later when the cancer that had taken his leg entered his lungs. Fox died nine months later.

Gail was not yet aware that her commitment to telling Terry’s story in pictures would set her on a new career trajectory, taking her from being only the third female photographer hired by United Press International to the red carpet as one of Canada’s most acclaimed and busy filmmakers.

“Terry Fox taught me one thing—that photography is about people,” she explains. “When he died, all of a sudden those pictures became precious. That’s what photography is about. And that’s what film making is about. You have to grab life as it goes by.”

Gail has won countless national and international awards as a director, photographer, producer and writer. She is perhaps best known internationally as director on the Netflix megahit Virgin River. Her television credits include Dark Matter, Murdock Mysteries and Heartland.

Gail’s primary focus is on telling women’s stories on networks and streaming services such as Lifetime, Netflix, Prime and Hallmark. In recent years, she has teamed up with her daughter, actor-turned-director Katie Boland, to make original films and documentaries including a biopic about iconic singer Rickie Lee Jones.

“I love doing female stories and I do a lot of them, because they are important stories. The Lifetime movies, as an example, are edgier. Producers will often save the emotional scripts for me.”

Shifting Focus

Her transition to the film industry began when she was hired by HBO to shoot stills for a movie poster about Terry Fox. That led to an opportunity to work with Canadian producer Bob Cooper on a movie starring Elizabeth Taylor, which was being shot in Toronto.

“When you’re shooting famous people, all of a sudden your work is in demand,” she says. “And then I made a short film about Wayne Pronger, who had cerebral palsy and wrote country songs.”

That film made it into the Toronto International Film Festival, which led to her acceptance in the Canadian Centre for Advanced Film Studies founded by Canadian director Norman Jewison (Moonstruck), who became a mentor along with legendary director Arthur Penn (Bonnie and Clyde).

“I loved the film centre,” she says. “There isn’t a day that goes by or a film I’ve worked on that I don’t think of something they said to me.” Then she laughs. “I went in as a rich photographer and came out a poor director.”

The Keys to Success

Gail admits the road to success in the film industry is riddled with potholes.

“It is very hard work, especially for women. There are times I’ve thought about quitting but my agent won’t let me. It’s not easy but I have to say, I’ve been very lucky. I know I’m a pretty good director because I know the camera, I know about people, I know about acting.”

Longtime friend and former Toronto Star colleague Rob Salem believes Gail’s accession is more about perseverance than luck.

“She came up in the competitive world of newspaper journalism back when it was pretty much exclusively male. With attitude. And her eldest daughter has been an actress since she was a zygote, so she knows how to work with actors. And finally, experience—her volume and variety of work is staggering.”

Former Toronto Star columnist and best-selling author Linwood Barclay credits her extreme work ethic as the key to her success. “Gail can’t not work,” says Barclay, whose novella Never Saw It Coming was adapted by Gail into a feature film starring Emily Hampshire (Schitt’s Creek) and Hollywood veteran Eric Roberts.

“Every shoot for her is like making a new family and it’s her nurturing style and enthusiasm that makes her such a good director,” he says. “She brings out the best in her crew and her actors and actresses because she loves them all and the feeling is mutual. She’s a true pro, not ruled by ego but by a desire to make the best movie or hour of TV she can.”

Creative Beginnings

Born in Toronto to legendary Canadian country singer Larry Harvey and his manager-wife Vergena, Gail grew up in a family that encouraged artistic endeavours. She was a free spirit who loved to draw, sing and tap dance from an early age. She caught the photography bug from the teenage son of the people her parents rented from.

“I would help him with his pictures when I was three or four years old,” she says. “But I wanted to be an artist. When I was a kid, I would spend all my time painting and drawing.”

It was only in her early 20s when she had an epiphany. On a trip to Europe, she took a camera with her to document her adventures.

“I remember thinking, ‘Oh, this is art.’ It had never occurred to me.”

Prior to working for UPC, Harvey worked as a flight attendant for Wardair and she says she loved travelling the world. But the photography bug had bitten hard. With her first pay cheque from Wardair, she bought a Pentax camera in a duty free shop.

When she wasn’t flying, Gail spent hours at the beach and around Toronto shooting with new friends who were photographers from the Toronto Sun.

They made an introduction at the Sun, and she sold her first picture of a windsurfer she had taken at the beach. Soon she was selling photos to all the major papers in Toronto.

Not all her newspaper colleagues were impressed.

“They all thought it was cute, since there were only two women shooting in Toronto at the time. One guy asked how I could be a photojournalist (as a woman)? What if there’s an accident and you have to climb over the guard rail of the Gardner Expressway?”

A few months later, Harvey was hired by United Press, and the rest is history.

A few months later, Harvey was hired by United Press, and the rest is history.