Clive Doucet reflects on building a better world for the next generation

“Grandfathers were magical creatures, much like unicorns,” says author and retired politician, Clive Doucet in remembering his summers with his grandfather in Grand Étang, Cape Breton.

“My grandfather was a unicorn to me. Unicorns are attached to magical times. We moved around by horse and did things that seemed magically connected to the sea and the land. He was 73 when I was 12. It was a shock the first time I spent the summer with him. I didn’t speak a word of French because my mother was English, but my grandfather and I really bonded. I learned to speak French. I learned about the Acadian culture and about how a sustainable farming and fishing community worked. Those summers with my grandfather were seminal moments in my life. They changed my whole life in many ways.”

Clive wrote about those times in his bestselling book My Grandfather’s Cape Breton published in 1980, but still in print today.

As Clive grew older and learned more about his grandfather, he began to see him as more than a unicorn — as a person with passions and difficulties, goals and accomplishments.

William Doucet was a pillar of the community, a leader and a steward of the land and water. He ably dealt with people and complicated problems in both French and English, despite his inability to read or write.

He is now the age his grandfather was during their magical summers together. Over 50 years later, he has returned to the village of Grand Étang to build his own house and write My Grandfathers House: Returning to Cape Breton — a sequel of sorts to the book he wrote in 1980.

Clive explains how the two books differ. “My Grandfather’s Cape Breton was about one boy and one grandfather. Grandfather’s House is a bigger story. It’s not just about two people. It’s about history, love and people who wear their years lightly. Most of all, it’s about people who haven’t given up their hopes for a better world, people of courage. I wouldn’t have seen that quality in my own grandfather when I was a boy, but I see it in the people around me now.”

Many have left the small towns and villages like Grand Étang. The once vibrant fishing industry is gone; farmers’ fields that were once rich with crops are windblown and barren. But the integrity and warmth of the village remains. “Now it is primarily retired people who keep the community alive, offering a simple life, some basic services, and the newly embraced economy of tourism.” Indeed, the area has become a tourist centre with its connections to the beautiful landscapes of North Inverness, the Cabot Trail, Cape Breton Highlands National Park and the pull of Acadian music, folklore and family connections.

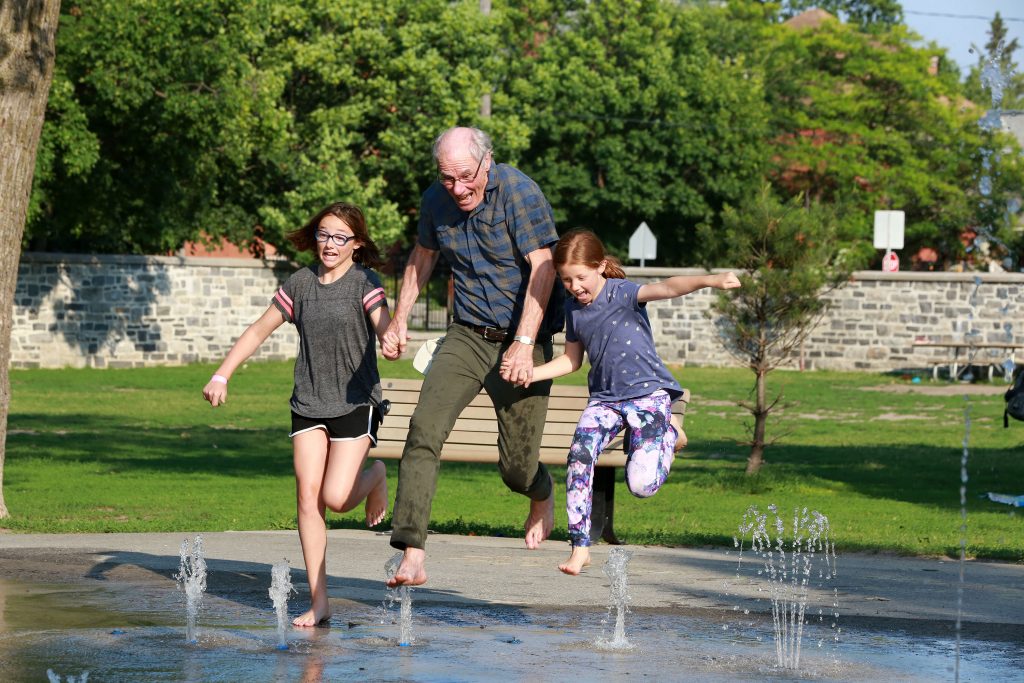

“There are at least two practical advantages to the changes,” says Clive. “The water is warmer and when my grandchildren visit, we can swim in the harbour. This would never have been possible in my grandfather’s time because the water was full of fish guts from the fish processing plant. Secondly, thanks to tourism, I can easily rent out my house for periods of time when I cannot be there. This provides some money I need to maintain the house and the property.”

“There are at least two practical advantages to the changes,” says Clive. “The water is warmer and when my grandchildren visit, we can swim in the harbour. This would never have been possible in my grandfather’s time because the water was full of fish guts from the fish processing plant. Secondly, thanks to tourism, I can easily rent out my house for periods of time when I cannot be there. This provides some money I need to maintain the house and the property.”

Maintaining his Cape Breton home is no easy matter, although Clive enjoys working outdoors and doing a lot of the labour himself. Like his grandfather, he is committed to stewarding the land and the water on his eight-acre site. Clive built the house in a beautiful spot on the edge of a cliff in Canada’s windiest region. He put 500 pounds of timber in the attic to protect the roof from wind speeds that sometimes reach 200 kilometres per hour. While strong windstorms have always been a feature of the region, climate change has led to an increase in the number and severity of storms up the coast. “I talk about this in the book, ”says Clive, “because there is no denying the effect of climate change on the sustainability of our homes and our livelihoods in both small towns and cities.”

Clive’s passion for creating and maintaining a sustainable, clean environment for the next generation is one of the underlying themes in Grandfather’s House. His thinking about it has been influenced by his experiences in the rural village of Grand Étang and in the urban environment. “City problems do not exist in isolation from the country. And vice versa. Farmers need cities that are successful, and cities need farmers to feed them. At the end of the day, we all share the same harbour, our planet. It’s how our lives fit within that larger harbour that will determine whether or not our grandchildren will have an easy or hard future.”

Clive grew up in St.John’s, Newfoundland and Ottawa. He became an urban anthropologist and worked as a public servant federally and provincially. He was elected to four terms as a city councillor in Ottawa. In 2004,he was named Canada’s greenest councillor. He was unsuccessful in his run for mayor in the last municipal election, despite a spirited and thoughtful campaign that provoked debate on some key issues.

“My political life in Ottawa taught me a lot. Knowledge is not the problem. We knew that the fishery was being destroyed by humans; we knew that our cities would have to deal with environmental issues like flooding, pollution, green transit, energy use and the protection of green spaces. The problem is not a lack of knowledge. It is a lack of political will to make responsible decisions, to take action and to resist lobby groups that pollute our environment in the name of the economy and corporate greed. Our elected officials — and the parents and grandparents that elect them — must demand and show leadership in environmental sustainability. We owe this to our grandchildren and the generations coming after them.”

Anyone who comes from the East coast and those who want to learn more about the Acadians and their place in Canada, will especially appreciate Clive’s latest book. Through storytelling and some solid research, he tells revealing and sometimes poignant stories about Acadian Canadians and their history, as seen through the lives of his grandfather and his family. The Doucet tribe goes back to 1632 and Captain Germaine Doucet, who fathered children in the New World of Nova Scotia. Clive offers stories about his ancestors ’experiences in what led up to the Seven Years War of 1756, the deportation of the French Catholic Acadians, and the return and rebuilding of the Acadian community. He is especially proud of his grandfather’s contributions and those of his father Fern Doucet, who became a world expert on sustainable fisheries.

Clive began every community newspaper column with a poem like this for 12 years. It was his way of making “hope” the beginning of each article, when the rest of the text dealt with tough stuff related to city growth and politics.

The more he despaired about society’s refusal to deal with real threats to the environment, the more he felt inclined to focus on hope. “Hope is the foundation of life and continuity for us all,” says Clive. “But it is up to us. We are the authors of our villages and cities. When I look around the village of Grand Étang, I am surrounded by hope. The people there have not given up. In their older years, they continue to work for a fairer, more secure, more exciting world. They inspire me.”

Clive has four grandchildren: Félix, Cléa and Évangéline are children of his daughter Emma and Sebastien Labelle. The fourth grandchild, ‘Little Emma’ is his son Julian’s daughter. It is probably no accident that Sebastien and Emma named one of their children Évangéline, who is enshrined in Longfellow’s poem of the same name. The heart-wrenching story of Évangéline and her lost lover Gabriel was inspired by the terrible circumstances of the Acadian deportation, when men and women were physically separated and made to board different ships.

Clive writes and talks about the joy of grandparenting today. “When I was younger, I didn’t understand the most important thing about being a grandfather. It’s not about having a house by the sea or a little farm. The most important thing about being a grandfather is that you adore your grandchildren and they adore you back.

One time, my granddaughter Cléa and I were out rowing, alert to the possibility of spotting a mermaid. Cléa cried out when she caught sight of a fishing eagle circling lower and lower in the blue sky. The eagle announced ‘I am, therefore, I am’ in the harsh cry of his species. I looked at Cléa and thought to myself, ‘I am connected, therefore I am.’ Like the eagle, our own voyage is a collective, not a solitary one.”

One summer, Clive’s 10-year-old grandson Félix said “When I’m grown up, I am going to bring my children here. No! My grandchildren.” Clive laughed. “Félix has a wicked sense of humour, but if he ever does bring his grandchildren it will be for the same reason I built the house, and how can that be foolish?”

“My grandfather was a magical unicorn and so much more. He taught me about what really matters by involving me in his life and inviting me into a rich, loving relationship. I try to do the same with my grandchildren, without lecturing or cajoling them. When they visit, they see rooms full of books and they can watch whales with the telescope I have set up on the deck. We don’t schedule every moment. They have times with me for adventure, exploring the sea and the land, and times for themselves to read and create art, to play and to dream.

In some ways, I hope they see me as a unicorn. But in other ways, I hope they do not. Unicorns are immortal. Humans are not. We need to live our lives now, in ways that appreciate the

wholeness of life, who love and nurture the next generation and leave a better place for them. I hope that my grandchildren will come to think of me as someone who tries to do this.”

My Grandfather’s House Returning to Cape Breton

by Clive Doucet

Nimbus Publishing Ltd., 2018. Available at local bookstores and Amazon.ca. Grandfather’s House was shortlisted this year for the Dartmouth Prize for non-fiction in Atlantic Canada. Clive generously donates a portion of his proceeds to the Stephen Lewis Foundation Grandmothers to Grandmothers Campaign, which supports grandmothers in Africa who are raising millions of young people orphaned by AIDS.