By Paul Gessell

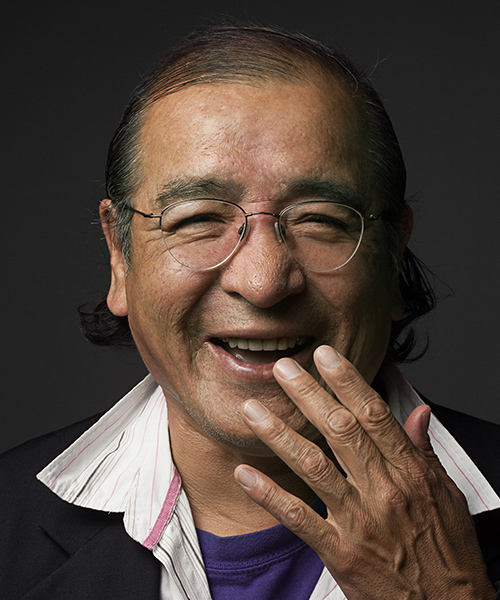

Tomson Highway’s latest book is titled Laughing with the Trickster: On Sex, Death, and Accordions. It is filled with many thought-provoking, hilarious and ribald stories. What else would you expect from this celebrated and playful Indigenous writer who claims he was born atop a snowbank?

Now, who is the trickster in this book? Is it the mischievous, shapeshifting, immortal trickster Weesageechak that inhabits Cree culture? Or is the trickster really the book’s author, the mischievous, shapeshifting, mortal man we know as the perpetually joyful Tomson Highway?

Now in his early 70s, this spawn of a snowbank—actually, he was born in a tent perched on a snowbank—first came to attention decades ago as a globe-trotting, classical concert pianist. “I’m the piano player from hell,” he jokes. “I have the chops to play Rachmaninoff and Chopin.”

After establishing his concert career, the shapeshifting Tomson focused on writing plays. His most celebrated are as The Rez Sisters and Dry Lips Oughta Move to Kapuskasing, which plumb the heart and soul of reserve life in the way Quebec playwright Michel Tremblay reveals the true spirit of the working class in east-end Montreal. Highway’s plays were followed by his magical novel, Kiss of the Fur Queen, in which a trickster, masquerading as a beauty queen, interacts with a family similar to the author’s.

And now Tomson is in a non-fiction period. In 2021, it was the autobiographical Permanent Astonishment covering his first 15 years of life, from that sub-Arctic snowbank to high school in Winnipeg. This year, it is Laughing with the Trickster, which is the text, in book form, of the Massey Lecture he delivered in five Canadian cities this past September detailing how language and religion can shape our lives.

English, Tomson writes, is a brilliant language, just not when it comes to descriptions of pleasure. Cree is terrible at making money but is very humorous: The word for white man is pronounced “moony-ass.” Or so Tomson says.

So, what exactly is a trickster? Tomson tells us that tricksters are never male nor female. (Tomson identifies as two-spirit, a mixture of male and female.) Tricksters are also known as shapeshifters, which Tomson claimed to be in Permanent Astonishment.

“S/he can change into and be anyone or anything s/he wants at any given point in time.” (Tomson has had various careers, from social worker to concert pianist.) “She can be a man, he can be a woman—the absence of gender in Cree facilitates the process—s/he can be an animal, most notably a mangy coyote. Or a rabbit. Or a spider.”

In summation, Tomson writes that a trickster is an entity “difficult to put your finger on.” That definitely sounds like Tomson, who has been delighting, surprising and sometimes baffling audiences for half a century. One suspects that all the academic types who attended Tomson’s lecture series were expecting something a little more highbrow than learning how to pronounce, in Cree, various usually clothed body parts.

Highway’s participation in the Massey Lecture circuit follows in the footsteps of such high-profile Canadian intellectuals as Margaret Atwood, Adrienne Clarkson, John Kenneth Galbraith and Michael Ignatieff. Highway can certainly be described as an intellectual, but with a naughty, mystical streak. That comes through in Laughing with the Trickster. That book, like himself, always seems to be hovering slightly above the earth, tethered precariously to reality, just like that Latin American genre of literature known as magic realism.

Consider Tomson’s autobiographical Permanent Astonishment. It begins with an author’s note explaining how the book was originally crafted in his imagination in Cree: “This is a shapeshifter book, residing in the space between fact and fiction, the fantastical place of memory and dream. It is a book imagined—and written in my head and in my heart—in what surely is one of the most joyful and funniest languages on Earth.”

The reference to that “space between fact and fiction” is reminiscent of the thinking of the late Canadian author Farley Mowat, who believed that writers sometimes must resort to fiction to find a truth greater than what straight facts can provide. In an interview, Tomson struggled to explain his own fact-versus-fiction philosophy but finally said: “The Cree style of storytelling is that we exaggerate a lot.” These are not exaggerations intended to deceive but exaggerations designed to uncover some greater truth.

Tomson believes we are placed on this earth to laugh and be happy. Dwelling on misery is no way to live, he insists. And that brings us to Tomson’s childhood experience with sexual abuse at an Indigenous residential school near The Pas, Manitoba. “I never think about it,” he says. “It’s water under the bridge for me.” He continues: “I am not what happened to me. I am who I want to be. That’s central to my way of thinking. I’m so busy having a fabulous time I really don’t have time to think about misery.”

Tomson prefers to talk and write about the positive aspects of his education, including the piano lessons he received at residential school that propelled him to his career as a concert pianist. The first lessons came from a nun, Sister St. Aramaa. “Wild moose couldn’t pull me away from that keyboard,” he writes in Permanent Astonishment. “I am smitten. I am obsessed.”

In the acknowledgements at the end of Permanent Astonishment, Tomson thanks his publisher, agent, relatives and other key figures in his life including the staff of the Guy Hill Indian Residential School. Rarely does one hear positive statements about Indigenous residential schools from Indigenous people. The politically correct thinking is to condemn the schools in their totality.

“I went to one (residential school) for nine years and had a fabulous time but I’m not allowed to talk about that in public,” he said in the interview. “We are being silenced, those of us who have anything positive to say about it, because there were a lot of us who had a wonderful time in the schools.”

Tomson Highway was born Dec. 6, 1951, the 11th of 12 children of Joe Highway, a caribou hunter, fisherman and champion dogsled racer, and his wife Balazee. In Permanent Astonishment, the family is portrayed as poor in a material sense but rich in laughter, endurance and daring. From a young age, Joe Highway had high expectations for Tomson and his brother, Rene, who came three years later. They were, in their father’s mind, destined to be princes of the north, the most famous inhabitants of the Cree village of Brochet in Manitoba, near where that province meets the borders of Saskatchewan, Northwest Territories and what is now Nunavut.

When the brothers were 11 and eight, they found two young orphaned eagles and adopted them as pets. The eagles invaded the boys’ dream life. “We rode on their backs and flew into the air and flew around the world,” Tomson says. That kind of dreamland and that reality merge seamlessly in his writing.At age six, Tomson was sent to residential school near The Pas. High school was in Winnipeg and university was in London at the University of Western Ontario, where he obtained a bachelor of arts, honours, in music in 1975 and a B.A. in English in 1976. After graduation, he spent seven years working as a social worker at various Indigenous communities. And then he dived into the arts, performing piano concerts, writing plays and books and becoming one of the best-known and most decorated, Indigenous persons in Canada. Tomson’s awards include several honorary doctorate degrees, the Order of Canada, theatrical and literary prizes for his writing and a Governor General’s Performing Arts Award that recognizes a lifetime of achievement in the arts.

Being Cree and being gay affects Highway’s writing process, he says. “What I appreciate about my sexuality is that it gives me the status of the outsider,” he is quoted as saying in a 1991 Toronto Life interview. “And as a native, I am an outsider in a double sense. That gives you a wider vision, a more in-depth vision into the ways of human behaviour, into the way the world works.”

Tomson’s vision has made him an icon within the Indigenous theatre world. Lori Marchand, managing director of Indigenous Theatre at the National Arts Centre, said when Tomson started the professional company Native Earth Performing Arts in Toronto in 1982, there was “nothing” in Indigenous theatre in Canada. “The fact that he undertook that work, it opened up the door for all of us who came afterwards.”

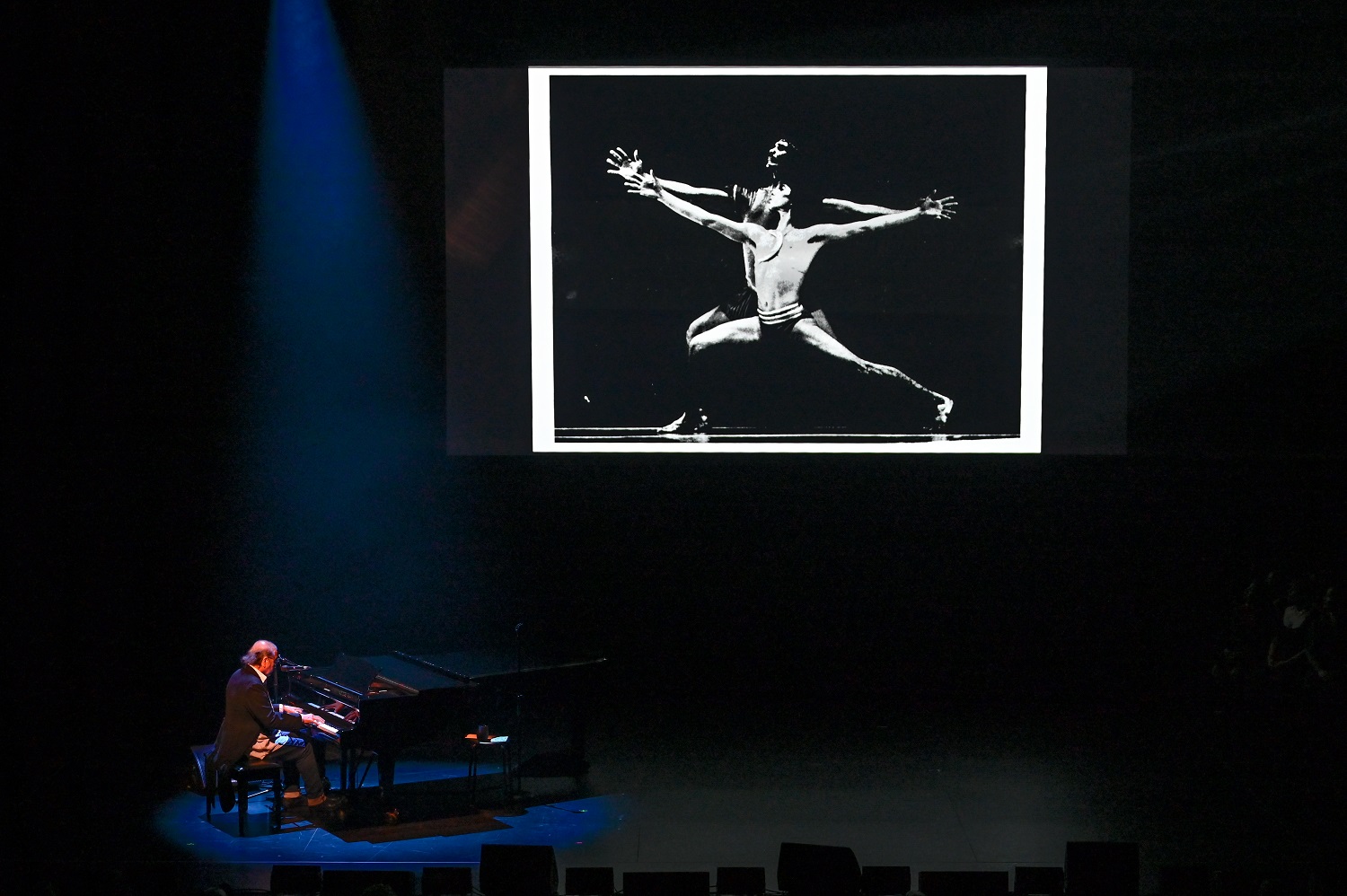

To thank Tomson for a life’s work, the NAC produced a one-night tribute this past summer entitled Tomson Highway: Kisaageetin (I love you/Je t’aime). The evening included staged excerpts from some of his plays and performances by Tomson on the piano. Some of the pieces were played while giant images of his late brother Rene, a dancer, were simultaneously projected onto the stage. There was also a composition, The Flight, played by Tomson along with his two grandchildren playing violins.

Milena and Marek Faucher, both preteens, are the biological grandchildren of Tomson’s partner of almost four decades, Raymond Lalonde, who had a daughter, Alexie, from a previous marriage. Tomson sees Alexie and her children as his own family. They all live a few blocks apart near Lac Deschenes in the old cottage community of Wychwood, which was swallowed up by Aylmer and then by the city of Gatineau.

“They are highly gifted children,” Tomson says of the grandkids. “They played perfectly; not a mistake.”

The NAC event was not just a tribute to Tomson but also, in a way, to his brother Rene, who died in 1990. Despite their three-year age gap, the two brothers were raised like twins, says Tomson. They were best friends and collaborators, with Rene choreographing movement and dance numbers in Tomson’s plays. For one more time, the two brothers were able to perform together again, virtually, at the NAC.

Rene and Tomson formed a strong bond as children. When Rene first attended residential school, the older Tomson would sneak into his brother’s bed at night to comfort the homesick younger boy. Many years later, as the 35-year-old Rene was dying of an AIDS-related illness in a Toronto hospital, Tomson would crawl into Rene’s hospital bed to hug and console him. Rene’s last words to Tomson were: “Don’t mourn me, be joyful.” So, Tomson believed from that day on his job was to be joyful to honour Rene. “Which is why you will always see me having twice as good a time as everyone in any given room, at any given time. I have no time for tears; I am too busy being joyful.”

In a rare interview, Raymond was quoted in a 1991 Toronto Star feature story by Judy Steed explaining the professional relationship between the two Highway brothers: “Tom and Rene talked on the phone all the time, three times a day, always in Cree. . . . I loved going to rehearsals when Rene and Tom were working. They are very different: Rene was not an intellectual, he was not agile with language the way Tom is. He wasn’t as educated. Rene played

on the street more; Tom is more into business, administration, writing. But together, in the theatre, they clicked. They didn’t have to talk, they knew what had to be done to get where they wanted to go. Rene would choreograph certain movements to accompany the words, telling actors when to turn, raise a hand, look around. It was as if he’d make people dance even though they weren’t dancing.”

So, what’s in store for Tomson these days? Well, the NAC has as a “goal” to offer some day a production of Highway’s rarely performed play Rose, a large-cast musical set on a reserve. Characters from some of Tomson’s previous plays make re-appearances. The script calls for working motorcycles on stage – definitely a challenge for any director.

And Tomson is supposed to be working on the second instalment of his autobiography. That book is to cover his life from age 15 to 30 and is to be followed by three other books, each one covering a 15-year period. At least that is the plan. But the aging trickster says he would love to retire. Really? He does not sound convincing. Tricksters, you see, are immortal. They don’t retire. They never stop. They keep us laughing and, as Tomson warns: “If we don’t laugh we will be dead.”